I have been treasuring the opportunity to read about other educators’ lives during this time, as they share with such rawness and candor. It helps to feel less alone.

Here are just some of the posts that have touched my heart and ignited my imagination in some way.

Care Is a Practice; Care is Pedagogical, by Jesse Stommel

Jesse shares about his Mom’s health challenges that drew their family to move across the country and their daughter’s early understandings of the permanence of death. He also describes the ways in which the Open Online Office Hours have brought educators from around the world together in solidarity.

During one of the office hours sessions, they learned that Jesse's husband was being laid off, news which is normally delivered in person, but came via a webcam this time. Finally, he recommends we carefully read our institutions reopening plans and attempt to discern the values being expressed and enacted.

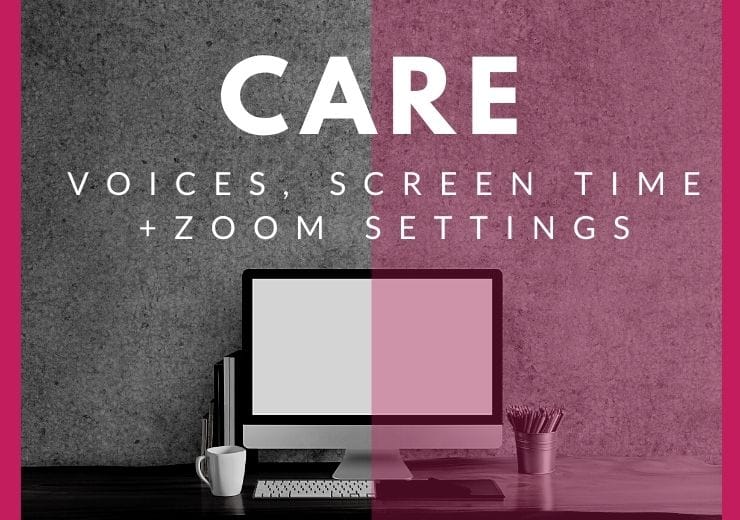

Voices First, Faces Second: Beyond the Tweet, by Maha Bali

I used to require my students to have their camera on during classes. This was in the context of teaching doctoral classes and I packed all kinds of privilege in my choice to establish those rules. Now, I can see things in a lot more nuanced of a way, though I always allow students to make that choice for themselves.

Maha reveals her own desire to be able to see the students she is teaching, but she also knows some of the reasons they may prefer leaving their cameras off. She describes other approaches we can use to have those more human connections beyond a stringent requirement. She asserts that we should first center students' voices, then attempt to get to see their faces. “Voices first, faces second.”

Flipping the Screen Time Conversation into a Meaningful Activity Exploration, by Maha Bali

Dave and I used to have very different approaches to our kids’ screen time than we do now. It was a maximum of one hour per day, with some days not having any time in front of screens at all. Now? Let’s just say they are engaging in school remotely right now – and have what we call “choice time” around here in the afternoons, which usually results in playing Minecraft. A lot of Minecraft.

Maha changed the conversation for me around screen time by thinking through it in the context of what is being done with those screens. Our kids have had the opportunity to play Minecraft with Maha’s daughter (“O”) probably ten times by now. We were able to connect them right as “O” was just starting Minecraft. At first, I was concerned about the many cultural differences I knew would pop up in there. But Maha’s humor and direct communication style made me less afraid and more excited about the tremendous opportunities before us all.

I think about context pretty much every day of my life.

We create way too many dichotomous choices in our lives and the lives of others. Context seems to always be the road toward better-discerned decisions and greater opportunities for connections with people who view things differently than we do.

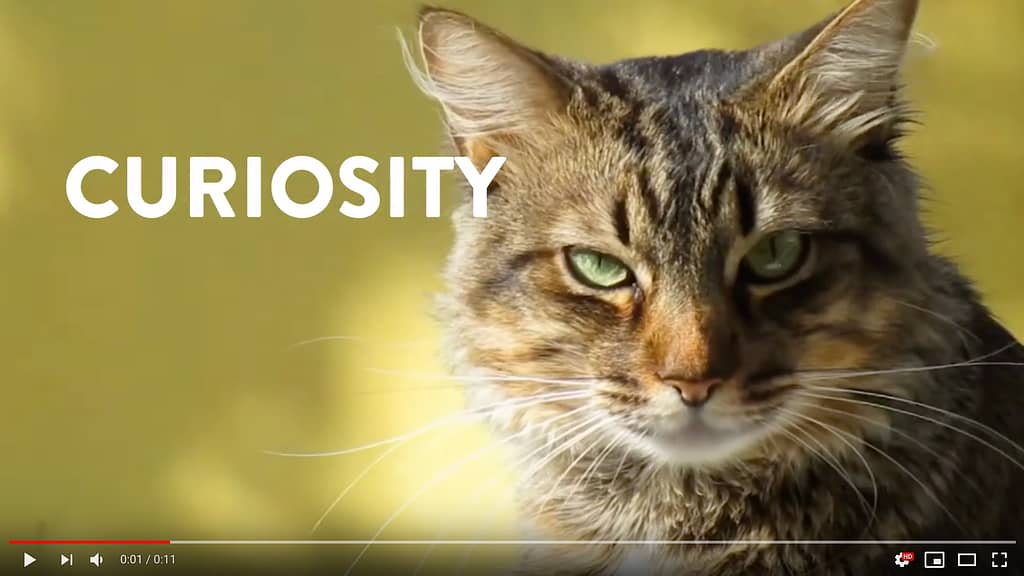

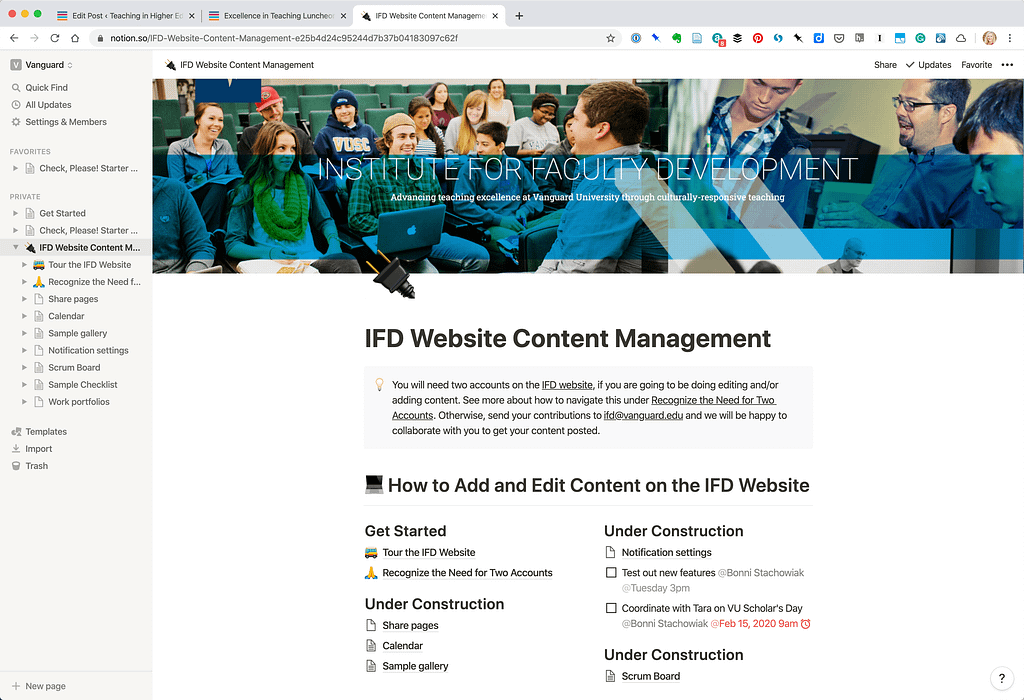

Video: Recommended Zoom Settings, by Teddy Svornos

I almost didn’t watch this video, thinking that I have settings pretty figured out on Zoom and so do my students. However, I was in for a treat. In two minutes, Teddy shares how he recommends his students set up their Zoom settings within the context of using a smallish laptop so that they can actively learn while participating in class.

Here’s a taste of what he recommends, but I totally think it is better to watch it.

- “Keep video on, if your circumstances allow.”

- “Each class revolves around a handout” (and how to not have it take over your entire screen, when he is sharing it)

- Make these non-full screen settings permanently, in settings

- Use gallery view, while he is sharing the handout, and side-by-side mode (change the size of that portion of the window, using the slider bar)

- Merge to meeting window – chat and/or participants (only works if you’re not in full screen, which I didn’t realize)

- Change to speaker view when he has a camera on his whiteboard

I recommend you subscribe to Teddy’s Tech Notes in your RSS reader of choice, as he is excellent at providing guidance on teaching, educational technology, and productivity.

If you aren’t yet using an RSS reader/aggregator, check out Inoreader. Laura Gibbs is the person who first told me about Inoreader. She has this post from 2015, which still reads as very relevant (in terms of Inoreader tips) today, about how she organizes things in Inoreader. I use folders, subscribe to all “email newsletters” now via Inoreader, so they come into my RSS reader vs into my email, and read/unread.

These are just a few articles (and one video) that have stood out to me in recent weeks. I'm grateful for the generous ways educators are acting in solidarity with one another during this awful time. I can see so much life and beauty amidst the pain and devastation.