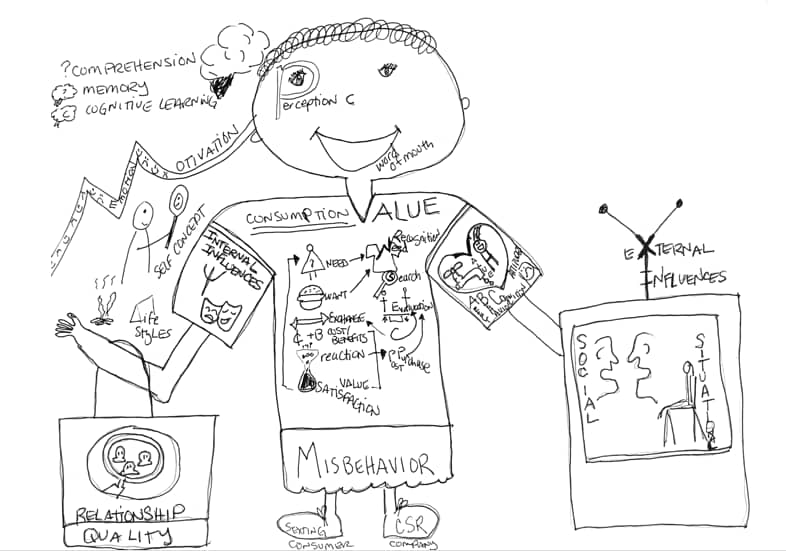

I've found pencasting to be a tool that is aligned with my pedagogy and valued by my students. Many of you have asked for me to share about my process, so I've created a How to Pencast video.

How to Pencast Video

In the pencasting video, I describe:

- What pencasting is

- Why it is vital to my teaching and instructional design

- Essential tools for pencasting

- My pencasting toolkit

- How I record and publish pencasts

Additional Resources for Pencasting

- Apple Pencil

- iPad Pro

- Doceri

- Mike Wesch's The Sleeper

- LiveScribe (product I used for years, prior to switching to a tablet-based method)

- The Sketchnote Handbook, by Mike Rohde

- The Back of the Napkin, by Dan Roam