I still feel a bit wobbly in my teaching this semester. Students’ facial expressions typically provide me with so many cues in my teaching. It leaves me wondering if I’m reaching them during our synchronous sessions since I have to rely on other gauges for assessing their engagement.

It has also been a tender time. Many of the students are graduating in December and wondering what life after college, during a pandemic, will be like… Some have been told that they need to leave home, not knowing where to go. Others have faced losses of loved ones or told there are only a few months left, at best.

Despite feeling like my class is less engaging than in other seasons of my teaching, the students have shared that they feel like the time we are together passes so quickly and that they are learning a lot. Here’s a look at how most of my synchronous classes are structured, in case it is helpful.

Before Class (10 minutes)

I start playing music about ten minutes before class. There will always be 3-4 people who join, but who typically leave themselves muted and have their cameras off. Sometimes, one of them will have a question, and that’s why they came on early. But it is mostly quiet, except for the music.

I run my class off of a web browser, for the most part, with the occasional .jpg graphic or short slide deck. I’m teaching a Hyflex class, which means that these synchronous classes are not required. Students have the flexibility to participate in an asynchronous activity that is not identical to the synchronous one, but addresses the same learning goals. Before class, I open all the tabs I will need during the class and place them in the chronological order they will be used.

I have found that if I build all the asynchronous activities, first, and then adjust them to be more suitable for a synchronous class session, it becomes a lot easier. I’ll write more about how I am developing asynchronous activities in future posts, but for now, the important thing is that there needs to be alignment in learning goals. Thinking that we can have identical experiences between asynchronous and synchronous experiences is not realistic and not a helpful aim.

Examen (5-10 minutes)

Each class starts with everyone answering two questions. They can answer aloud, though most choose to answer in chat (either publicly or privately). Each question starts the same way: Since we last met… Then, the second half varies:

- What brought you life?

- What took life away?

I share my answers to those questions, as well, and comment on some of the answers that were shared with the entire group. This has helped us bring community into our learning, during a time when it is harder than usual to get to know each other in this context.

One thing I already know I need to improve for next term is to incorporate this practice into the part of our learning community that engages asynchronously. I would ideally like it to be something that could be perceived as not taking a lot of time, but would give them the opportunity to share either privately or to the entire class. I tend to move away from discussion boards, since most learners have had such awful experiences with them that there’s so much unlearning to do in order to get going with them that I often consider other options, first.

Some kind of ongoing way of documenting our collective answers to these two questions might be interesting, using maybe Padlet or some other kind of more visual tool.

Review (10 – 15 minutes)

This class has a fair amount of new vocabulary for the students. We often begin by doing retrieval practice. I have flashcard decks in Quizlet that we will work through to review by playing some of their solo games, or by doing a few rounds of their Quizlet Live game.

A listener recently recommended Quizizz, recently, and our daughter has loved getting to experiment with it (she’s playing a game right now, in fact). I have been reluctant to try it in my current class, though, since we are in a groove with Quizlet and there’s no need to change things up at this point.

Dave recorded some short videos that teach them how to memorize the 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. They can list them 1-7, or descend from 7-1. They instead can have a number listed off and they can tell you the corresponding habit. Or, if you state one of the habits to them, they know the associated number. Dave learned about peg words from when he worked at Dale Carnegie, though mnemonic peg systems come up in other contexts, as well. Sometimes, we get started in the larger group and then go into breakout rooms for further practice.

Main Activity (20 minutes)

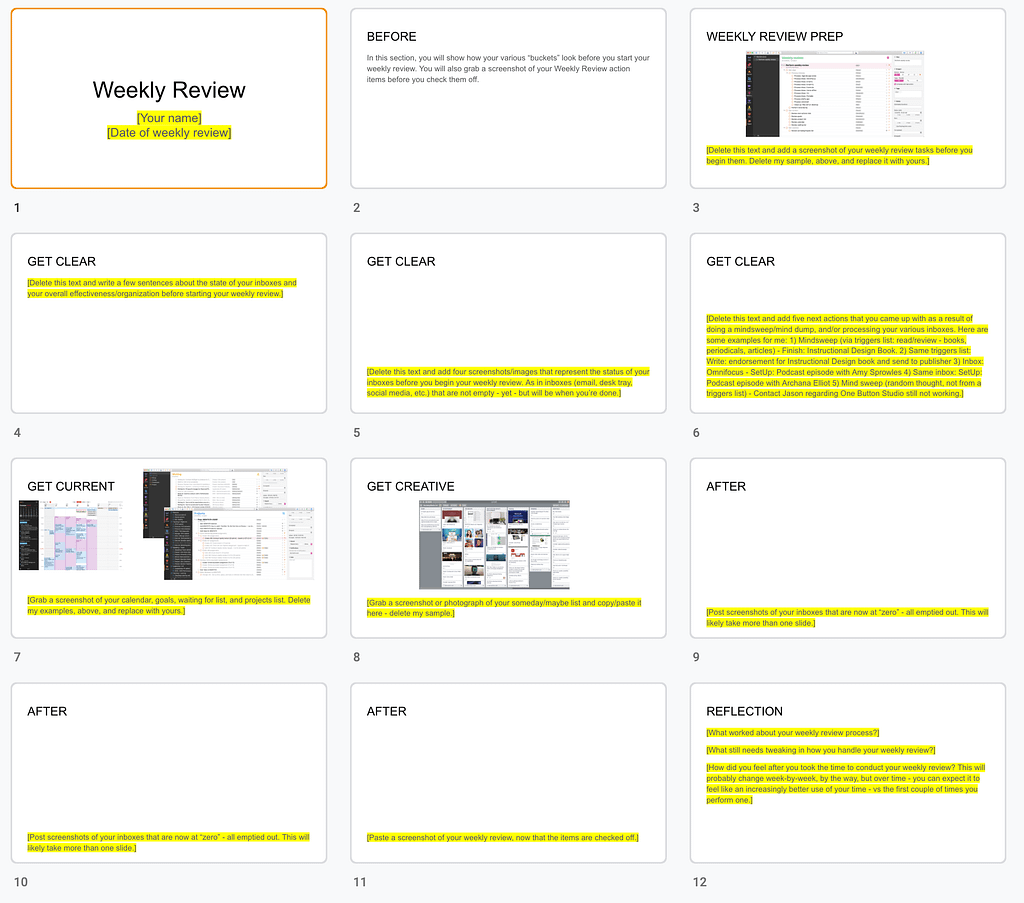

The vast majority of the time, the main activity for the session is building upon something they have already learned a little bit about. For example, they recently read the chapter in the Getting Things Done book about reviews, which emphasizes a process called the weekly review. All reading assignments in this class are expressed in the form of a quiz in Canvas (our LMS). By this point, they will have uploaded their notes on the chapter inside the quiz, along with some questions that test for understanding and some reflection prompts.

I mentioned no longer being able to get as many cues from facial expressions. Instead, I structure exercises to make their learning more transparent, often through some kind of a collaborative document they work on with others, or an editable document they work through on their own. In the case of the collaborative document, I can see their work as they engage in it. When they work independently, I have them export their work as a PDF and upload it to our LMS, partially as a means for taking attendance – but mostly to be able to see their learning process more clearly.

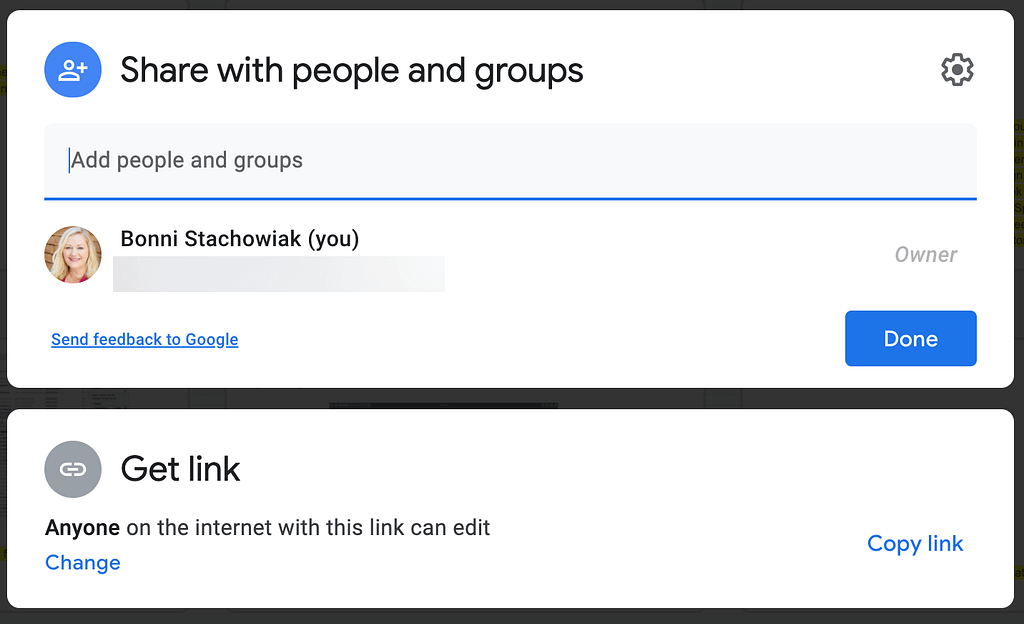

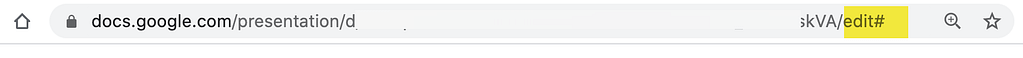

Most weeks, I set up a set of Google slides that have permission for edits to be made. Then, I share the entire document to the class and have them work in breakout groups on some portion of the slide deck. Alternatively, I edit the link to the document to say copy instead of edit at the end, which means that anyone who clicks the link will be given the option to create a copy of the document (instead of messing with my original).

In this case, students started building their weekly review process in class. They are accustomed by now that any text that is highlighted should be deleted and replaced with their information. They also are used to the fact that I will often have sample screenshots of what my process looks like, which can then be replaced with screenshots of their weekly review, as they build it.

If you want to try this kind of activity, you can learn more about it from Teaching Effectively with Zoom, by Dan Levy. We talk about this approach in episode 324 of Teaching in Higher Ed and he also shares about it on the Teaching Effectively with Zoom book resources website. The most common mistake I have made so far is sharing the file with students without first changing the settings to allow for others to edit. It’s an easy fix, of course, but I would always still rather have it set up correctly to begin with…

I write more about this process in my post: How Do You Make Zoom Breakout Rooms Less Boring, if you want to learn more.

Class is officially over at this point. I only have about 20 students in the class, so taking attendance at some point along the way is relatively easy. I let them know that their participation points will be recorded and that the official part of class has concluded. I let them know what chapters we will be covering in the next segment and ask students to give some kind of indication if they’re planning on coming back after the ten-minute break, so I know about how many to expect.

The After-Party (45 – 60 minutes)

I was intrigued by Mike Wesch’s mentions of how he creates a single .MP3 of all the reading for his classes each week. Given that he is the author of his textbook (The Art of Being Human), I suspected he didn’t have as much of a challenge trying to navigate copyright issues the way some of the rest of us might. Still, I knew that especially since the context surrounding the Getting Things Done book was likely so unfamiliar to many of the students, it would be good to help them through that.

I decided to do an abridged version of the assigned reading, with stories from my life of how the concepts have impacted me. We go through the questions from the quiz, together, though in a couple of cases I ask them to still provide answers, if it turns out to be essential that I get their personal reflections on a particular topic.

The feedback from students on “the after-party” sessions has been edifying. They tell me that blocking off this optional time helps them to get a jump start on the week’s assignments. They like learning in community and appreciate the way in which I make the reading more personal by sharing additional stories.

The After-After-Party

There is almost always someone who would like to stay after the after-party to talk one-on-one. These are some of the most life-giving conversations I have had in recent months.

Next Steps

I’m reasonably happy with the structure as I have it. I wish I had more polls populated in advance, but there hasn’t been enough time for everything I would like to try. I’m also intrigued by streaming platforms that take the possibilities beyond Zoom. One I have been experimenting with is called OBS Studio.

I also would like more times to bring the students’ stories into our learning community, from the pre-work they did prior to class. If I were going to do that, I would need a streamlined way of determining, in advance, if I had the person’s permission to share their example. When I have done things like that in the past, I would either ask via email, or one-on-one – just prior to the start of class. These days, I would need something more automated, perhaps by asking within the quiz (a question that the “right” answer could be either yes or no, potentially).

What about you? What's working for you with how you're structuring your synchronous class sessions? What challenges are you experiencing?