On-ramps: Reflections on the 14th Annual Open Education Conference

At last week's OpenEd17 conference, Jim Luke introduced the idea of having on-ramps for faculty to get on board with open education initiatives at our various institutions.

Ever since then, I have been captivated by the analogy of on-ramps as a means of supporting learners.

- In what ways did people provide me with ways to take my learning further regarding open education at OpenEd17?

- What have I discovered as a better means for introducing students to new ideas in my teaching?

- How do we address learners that are already speeding down a domain of knowledge's highway and have different needs to enhance their own learning than beginners do?

It seems like too daunting a task to attempt to give an overview of everything I discovered at OpenEd17. Instead, I will highlight a few key findings here, and assure you that my list of future potential podcast guests is larger than ever.

Start Somewhere

The first morning of the conference, we got to hear from a panel of students from Santa Ana College. They were articulate and celebrated what having open educational resources (OARs) in their courses has meant for them.

One of the panelists stressed that if faculty expect stellar assignments from their students, we should expect the same quality of work from ourselves. The overall message at this point in panel was that we should “just do it,” and start somewhere with our open education efforts.

Open Textbooks

I have been sharing recently that I'm embarking with my doctoral students on our first-ever open textbook endeavor. We are very early in the process (class just started last Saturday), but are all completely jazzed about what's possible.

Robin DeRosa's blog post on her open textbook efforts has been incredibly helpful to me, in considering how to get started. I decided to use Pressbooks for the composition and eventual distribution of the open textbook we will be writing.

Pressbooks is built on the popular blogging platform, WordPress. I am already familiar with WordPress, since that's what the Teaching in Higher Ed website uses. I was able to attend a session about the roadmap for future iterations of Pressbooks. They appear to be quite an innovative company and I'm excited to see what we are able to produce, using their service.

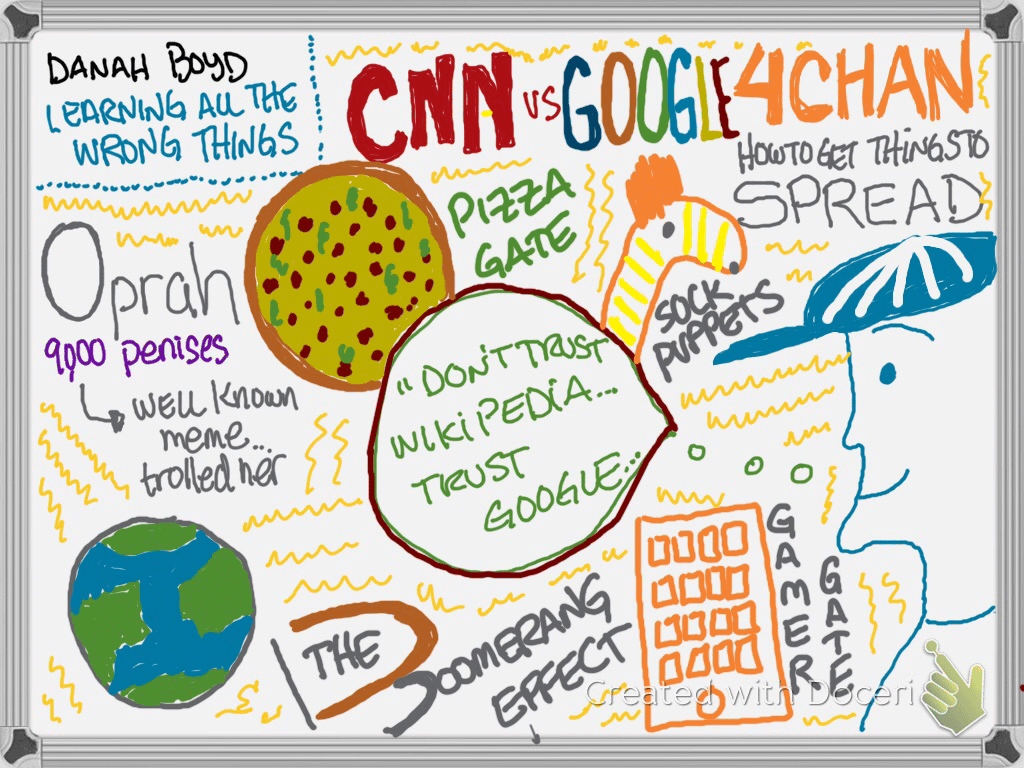

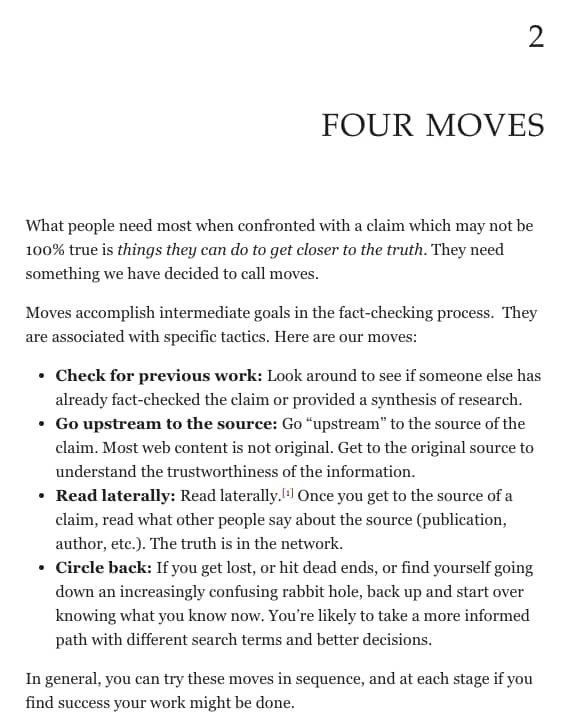

Mike Caulfield has published an open textbook using Pressbooks. His Web Literacy for Student Fact Checkers is an excellent source for helping to grow information literacy.

You can view Mike's presentation about the Digital Polarization Project online, thanks to Robin's filming efforts at OpenEd17. He also made his slides available online.

That's just the beginning of what's available through open textbooks. The Ohio State University Library has a great list of ways in which to search for books, using different websites.

Using already-available open textbooks is just the beginning of what's possible in open education. Many presenters stressed how faculty enjoy the ability to customize open textbooks to best meet their needs.

We were also encouraged to not replace one passive tool (a traditional textbook) with another passive tool (an open textbook). There are many ways in which we can make open educational resources engaging and active.

Keep Going

One way I am getting started is through OpenTextbooks. But, that is just the beginning, I know.

The OER (open educational resources) World Map is brimming with possibilities of where to possibly head next.

I hope to find colleagues at my institution who are ready to begin exploring how we might better serve our students through open education, even if it means starting in the smallest of ways.

Ken Bauer describes well the failures we will experience if we try to introduce too many new tools to faculty too quickly. He also shares questions he has, after attending OpenEd17, himself.

If you want to get more of a taste of what happened at OpenEd17, here's an OER video Digest that shares much more than what I have in this post.

Gratitude

I am thankful for all the people who gave so generously at OpenEd17. It was wonderful to get to meet some friends in person for the first time, while reuniting with other friends I haven't seen in a long while.

It all reminded me of some of the writing that Maha Bali did, after she met some friends in person for the first time at OER17. The experience is difficult to describe. I will treasure the opportunities to be in-person with such magnificent and inspiring educators and appreciate that we have such wonderful ways to stay in touch.