I've been inspired by Doug McKee (past guest on the Teaching in Higher Ed podcast and co-host of the Teach Better podcast) on a number of occasions.

In this case, I've been inspired by his courage to share his course evals online and reflect on what worked, what didn't, and what changes he will make in each course he teaches.

His recent post describes how he extracts value from course evaluations. I will follow a similar process below.

Fall 2014 course evaluations

At our university, we don't typically get our course evaluations back until well into the next semester. I received mine on February 20, 2015, which is sooner than they've been in past years, but still not soon enough for me to have made any significant adjustments to this semester's courses.

Those of us with tenure only have half of our courses evaluated each semester, creating a bit of a gap in the feedback process. Still, there are lessons to be gleaned each time I review the evaluations.

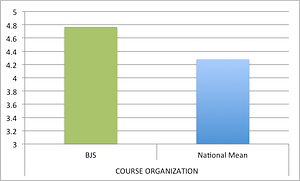

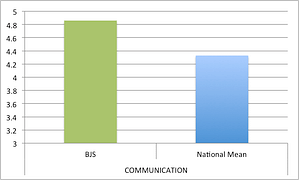

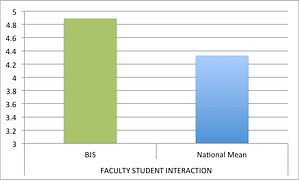

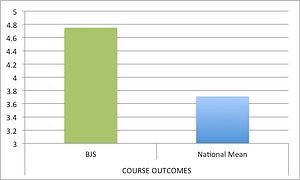

Quantitative results

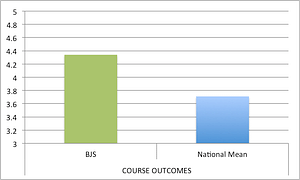

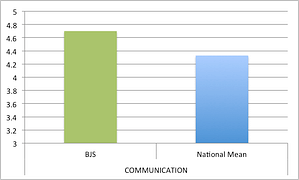

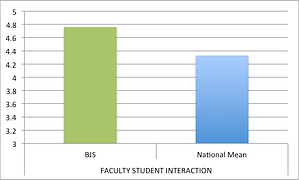

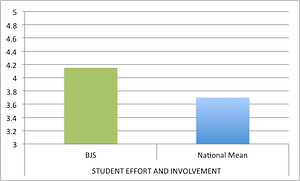

In both classes that were evaluated (Introduction to Business and Sales and Sales Management), the evaluations were rated higher than the national average. This feedback is typically not very valuable to me, since having my institution's data to compare myself to might be a better data set to use.

However, there are some detailed questions toward the end of the quantitative section that tend to help me put things in perspective. The items that typically help me remember who is was who was providing me feedback include:

- What grade are you anticipating in the course?

- How much effort did you put into the course?

- The workload for this course was _____ (heavier, about the same, lighter than) other courses you took this semester.

Sometimes, there will be one or two students who anticipate earning a D or an F in the course. In those instances, there are also anomalies on the quantitative results such as one person that marks that I didn't have a command of the English language, or that I treated people unfairly, based on their gender. I haven't ever been marked down for not speaking English well, or treating people unfairly, except in those cases where one or two students anticipate not earning a passing grade.

I realize it is correlation, not causation, that I'm describing here. However, I have a sneaking suspicion that perhaps in those cases, it has less to do with me needing to work on my ability to speak English and more to do with me needing to keep a pretty thick skin during the course evaluation process for those students with more of an external locus of control who aren't likely to pass the class.

Introduction to Business quantitative results

Sales and Sales Management quantitative results

Qualitative results

I find the qualitative data on course evaluations to be far more beneficial for me. I often wonder if a simple net promoter score might be able to take the place of all the other quantitative data.

Of course, I recognize that I don't have access to any institutional data. I just see my raw scores and the national mean. It seems like a whole lot of time and expense that goes into data that isn't very actionable in my case. However, perhaps it is more beneficial for my institution than I realize.

Our quantitative data essentially gets to the question of what worked and what didn't, though it isn't phrased in those exact works. Here are the results from my fall classes.

Introduction to Business (n=29)

What worked:

- Pencasts (n=6)

- Everything (n=5)

- EdTech tools (n=4)

- Interactive teaching style (n=4)

- Business plan project (n=3)

I am not including those comments that only came up once or twice.

One of the most humorous comments to me was when one student said what helped her learn was “Dr. B's calmness.” Wow. That's not something I get every day. Enthusiasm? Yes. But, calmness? That's a first.

What didn't work:

- Everything worked (n=9)

- Case studies (n=4)

I am skipping the two other comments that only came up once, though if you're interested, one student didn't like that I had them use Zotero and another didn't like that I had reading assignments in the course. Can you imagine that? A professor who assigns reading?

What I think is interesting about the case studies is that there were a number of comments on those items about them not being graded. Therefore, the students indicated that they didn't take them as seriously and didn't learn as much from them. I feel a bit stuck in my thinking between Ken Bain's advice to have there be opportunities for feedback before any grade gets assigned to something… and the accountability that comes from a stricter grading process.

I do look over all the students' cases in the class and there are points associated with them. However, the vast majority of the time, the students walk out with the full points and they don't feel the pressure to perform well.

Sales and Sales Management (n=16)

What worked?

- Role plays (n=3)

- Real-world scenarios/experiences (n=9)

- Sales challenge #3 (where they visit a company and do a final role play with a business professional they've never met) (n=7)

- Increased confidence (n=3)

- Relationship with the professor (n=3)

I skipped those comments that only came up once or twice.

What didn't work?

There weren't any items that came up more than once. However, I do plan on making changes as to the accountability on the blogging assignments when I teach this course in the future. I've started using a Google doc form to track submissions and my first trial run was a success.

Next steps

I've taught both of these courses many times (Intro to Business 30+ classes and Sales and Sales Management 10+ classes). I write new exams each semester, in an attempt to lower the opportunities to cheat. I also bring in fresh examples of what's happening in the business world each class session.

There are many affirmations in the assessments above that encourage me in my teaching. I commit to making the following changes next time I teach these courses:

- Use a Google doc form to track blog submissions, as described above, and do not waiver in the slightest on the due dates/times.

- Consider being more stringent in my grading of the cases and perhaps having the students be required to complete them as a group before they come to class on the day they are being discusses.

- This one isn't related to the evaluations, but I also want to start showing students a TurnItIn.com originality report before they submit their first assignment. It can be just one more way I can minimize the potential for academic dishonesty.

[reminder]Have you received your course evaluations back from last semester yet? What changes are you implementing for the next time you teach those classes?[/reminder]