The Question

I received this question from one of my doctoral students:

I really have no idea how to create a “brand” or how to create my blog to reflect who I am. Do you have any suggestions on how to figure out who I am, in the land of technology?”

Her question was so powerful that I wanted to share my thoughts to a broader community and invite others to provide suggestions to her, as well. In my reply to her, I'll consider:

- What is a personal brand and is that the “right way” to talk about our online presence?

- How do our blogs and other social media help to reflect who we are?

- How do we figure out who we are, when we're online?

My Response

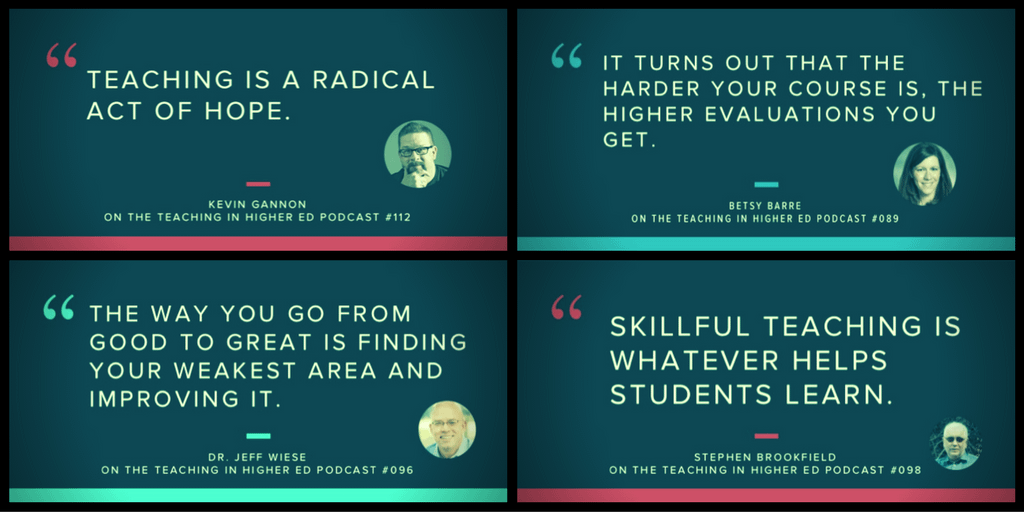

Let me start by saying how glad I am that you're asking these questions. Part of what has gone wrong with social media in certain contexts is that others haven't pondered in this way, before engaging online. Those of us who are more present online rarely stop asking these questions. Recent examples of these kinds of reflections include:

- My friend and his husband just adopted a beautiful baby girl. They are reflecting on how much they want to share about her online and in what context.

- A friend from college just announced that after the worst year of her life, that she and her husband were now separated, as of New Year's eve. She shared that she usually prefers to keep all her posts on Facebook positive, but she knew people would want to be aware of this change in her life.

- Many educators pondered how to return to the classroom, after the results of the Presidential election had been announced.

Personal Branding

The first time I remember having someone attempt to convince me that I was needed the same thing that my breakfast cereal did, was in a keynote talk given by Tom Peters in the early 90s. Cheerios needed help being identified and valued in the minds of consumers. And I needed help being identified and valued in the minds of current and future employers.

Starting today you are a brand.

You're every bit as much a brand as Nike, Coke, Pepsi, or the Body Shop. To start thinking like your own favorite brand manager, ask yourself the same question the brand managers at Nike, Coke, Pepsi, or the Body Shop ask themselves: What is it that my product or service does that makes it different? Give yourself the traditional 15-words-or-less contest challenge. Take the time to write down your answer. And then take the time to read it. Several times.”

I was intrigued, but also wasn't sure that I wanted to be some big corporate brand. Peters also wrote about more of us being freelancers, and at that time, that idea scared the heck out of me. The idea of an A-Z guide for my personal brand seemed too inauthentic for whatever it was I might attempt to do online. Yet, I didn't want to leave the results of what happened whenever someone inevitably Googled me in the hands of others.

Blogging and Social Media as Reflections of “Us”

Finding a voice online is difficult in the same way that figuring out who we are and who we are becoming when we're in-person is hard. We can certainly opt to hide all sorts of things about ourselves when we're online, but we can do that when we're face-to-face, as well. Greg McKeown warns us that thinking of ourselves as a multitude of skills is dangerous and that rather, we should consider our one main distinctive that we want others to perceive about us.

For me, that answer took a long time to come by, but I'm a teacher. That's what I do. That's what I'm good at. That's what I think about, constantly. When I blog or participate in social media, my primary focus is going to be on teaching. These days, I often get to be a teacher of other teachers, which brings me great joy.

In one of my doctoral classes, our professor recommended that we think about who our “stick figure is…” That is, who is it that you serve? Who is your audience of one? Rather than thinking about a broad, target market, he proposed that we find one person who we can always consider ourselves “talking to” when we blog, or give voice to our thoughts in other ways.

Adding Value Online

Once we have started thinking about the primary way we might be able to serve others and who one of the people we provide value for might be, we then can think about how to express some of that online. It can be intimidating to do this for a whole host of reasons, including that it's hard to be authentic, because it requires such vulnerability.

- What if I don't have anything to offer?

- What if I'm wrong about something?

- What if I wind up changing my mind about something, but now my old thoughts are still out there?

- What if I wind up being bullied or trolled online, the way so many others have in the past?

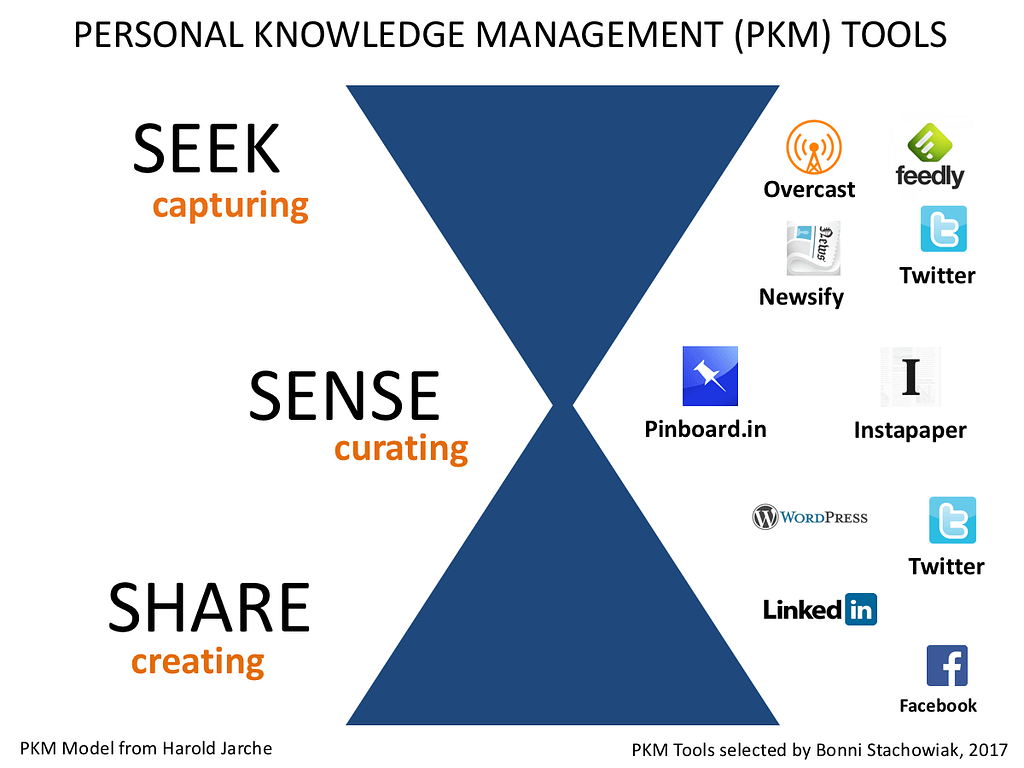

One way to get started is to think less about creating original content and instead provide value by seeking out others' content, making sense of it, and then sharing it.

Become a Curator

The most extreme example of being an expert curator is Dave Pell. He makes his whole living reading the news and then synthesizing it for those of us who don't have time to read 75 news sites a day. While I suspect you won't have time to go to that kind of extreme, as you consider your primary distinctive, hopefully you're regularly consuming news, resources, and other information in that area.

Here's a less-extreme examples of curation around a personal brand. Mike Taylor is an expert in the training and development field who I've been following for years now. Mike's LinkedIn profile is reflective of someone who has done the work to articulate and refine the way others come to know him. In his own words, he is:

Exploring the intersection of learning, technology & social media”

As 2016 ended, Mike created a series of curated posts, all around the theme of 12×12. 12 posts that each contained 12 items. Here were a few that caught my eye:

Next Steps

None of what I've described above is easy. This journey is best taken in small steps and with the realization that you'll never be done. I wish you the best as you start down the path and hope others will share their advice with you, as well.