This article was originally posted on EdSurge and is part of the guide Toward Better Teaching: Office Hours With Bonni Stachowiak. You can pose a question for a future column here.

Dear Bonni, I’m a brand new faculty member. I do not have formal training in pedagogy, except one measly adult education class from undergrad. I have a question regarding how you and others approach accommodations for those who are reluctant, resistant, or defiant to going through official channels at the university.

How I figure it, there are a list of things I find reasonable for all students—letting them stand or wiggle when they are having problems with attention or sleepiness, taking extra time to answer questions for assignments and projects, moving at a pace that is comfortable for the slowest in the group when we are on-the-move for class, etc.

However, students who ask for extra time on tests/projects, high levels (30%+) of extra credit, or to make up work weeks or months later, without having responded to any communications or requests for updates/accommodation needs… and still do not go to the Office of Accessibility… am I being a hard ass? How much do you bend?

I have 22 students all on the exact same schedule. I do not imagine that our program is their only or top priority, but I also do not imagine that it is fair to let some make up months of past due work to improve a grade from a previous semester or give extra time on evaluations without medical justification. Am I being too much of a hard ass?

—A new faculty member wanting to do the right thing

Candidly, your letter has been taking a back seat to questions I felt more confident in answering in recent months on EdSurge. I wish I had easy answers for you. What I have, instead, is nuance. No hard and fast rules exist, when it comes to navigating these spaces. I hope my messy experiences provide some ways of thinking differently regarding these decisions about your pedagogy.

You asked a couple of times in your message if you were being too strict. In general, I have found when I begin posing those questions to myself, I am likely not looking at things clearly. More so, I am likely not recognizing how complex students’ needs are—including those who might need accommodation.

There’s still a great deal of stigma around disabilities—learning-related, or otherwise. I have, on more than one occasion, witnessed faculty expressing disdain for the accommodation notifications that are sent to them, instead of grateful for the heads-up that their help and support is needed. It makes sense to me why students wouldn’t want to disclose their challenges, particularly when they could not be assured that it would actually help them in their learning any better than trying to go it alone.

There’s an air of suspicion among far too many faculty that students are attempting to use their diagnosed learning disabilities as a way to get preferential treatment that is unwarranted. Mike Caulfield, director of blended and networked learning at Washington State University Vancouver, tweeted about this misnomer back in March of 2019:

“I find it amazing that so many professors think access accommodations are easy excuses taken lightly by students, when the truth is that most students would love nothing more than to be see by a professor as “normal”

Caulfield then shared about a family member who has an accommodation, but does not disclose it at the start of most of her classes. She is too concerned that as soon as the professor becomes aware of her situation that she will be defined by her disability. “Every action is going to be interpreted through that lens. Even your normal behavior gets pathologized by others,” Caulfield conveys.

The implicit biases surrounding disabilities are ever-present, even if we aren’t able to see them in ourselves. Another common bias surrounding accommodations is to think of students requesting them as lazy. Devon Price, a social psychologist, writes in an essay on Medium

“if a student is struggling, they probably aren’t choosing to. They probably want to do well. They probably are trying. More broadly, I want all people to take a curious and empathic approach to individuals whom they initially want to judge as ‘lazy’ or irresponsible.”

Price’s last point about taking more of a curious approach reminded me of how important your question is to your doing just that, by reaching out. The reflecting you did around accommodations we can all make in our teaching to help students in their learning is wonderful. Getting students moving, over-communicating your expectations, and varying your pacing to reflect differing processing needs can all contribute to creating an environment more conducive to learning.

When it comes to deadlines for assignments, my approach varies widely. I found that when teaching as an adjunct in a doctoral program, both the culture of the program, along with the types of students who pursue their education in this way, contribute to me being less strict with deadlines. I have two days per week in which assignments are due (Tuesdays and Saturdays), but I let students know that as long as they are caught up by the start of each week (on Mondays), that they will be able to take advantage of the scaffolding that is built into the course structure.

The issue of stigmas I described earlier is particularly pronounced in doctoral programs. David M. Perry, writer and historian, writes in an article in Pacific Standard that while data does not exist regarding the rates of disability within U.S. doctoral programs, that there has been some research done on mental health, specifically. “The results are terrible,” Perry argues, noting the high rates of suicide, sexual harassment, depression and anxiety reported in a study involving 500 economics students.

There is no easy prescription to remedy these challenges. However, a big part of moving toward a more sustainable path is to remove the stigmas that exist and to normalize help-seeking behaviors.

My undergraduate courses have tighter deadlines. In fact, the ability to accomplish tasks by a certain date is an important measure in these classes. As an example, I teach a personal leadership and productivity course. It focuses on topics like setting goals, task and project management, email maintenance and calendaring. A big part of the class is being people of integrity to do what we say we will do—and that includes getting things in on time.

However, even in my undergraduate courses where I am stressing deadlines more heavily, I do build in some practices that allow for the occasional missing of a deadline without it having a big impact on a grade. This approach looks different depending on how I have structured a course. Sometimes, it might be to omit a couple of the lowest scores on low-stakes assignments. In other cases, when completion is more important for building a foundation for learning, I allow for a couple of instances for assignments to be turned in late (without a requirement to explain the reason why).

Each class policy we put in place should be based on whether or not it supports the students learning in some way. We also need to be humble about the fact that we lack the knowledge to always be able to make decisions that are defensible. I used to “ban” laptops, for example, not realizing the impact of this choice on all students. As Matthew Cortland, a writer, lawyer, and self-professed public health nerd, stresses, “even with exceptions for students who really need laptops, bans introduce discrimination and unfairness to the classroom.”

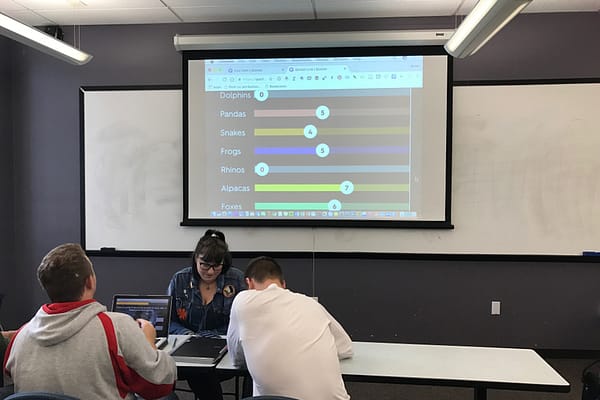

While I am still aware of the challenges that digital distractions can bring in the classroom, I prefer to think of the times when I propose that students put their digital devices away for a bit as an invitation I am making to them to a unique experience for learning. I also remain aware that there should be times in class when students are welcomed—and even encouraged—to use their devices.

You asked at the conclusion of your message to me: Am I being too much of a hard-ass?

From the little information I have, you do seem to be over-simplifying the choice that it can be for students to decide to seek accommodations. My advice is to become more familiar with just how much stigma still exists to seeking that kind of support and the discriminatory ways in which far too many faculty respond to these legally-mandated steps.

You are not alone in this, by the way. I used to find myself without much of an understanding of how those with learning and other disabilities are discriminated against in higher-education spaces. I found greater capacity for empathy and a greater awareness of the issues by following these hashtags on Twitter, along with the list of people I have curated to follow on Twitter, linked to below.

Hashtags:

Twitter List:

Disability Advocates and Educators

Extra credit goes to those who browse Dr. Amelia Gibson’s syllabus for her disability informatics course.

Update

Someone commented on Twitter that another piece of advice I could have provided this person on my original EdSurge column is to suggest that they consider using a Universal Design for Learning (UDL) approach. I appreciated the recommendation (there was so much to say!) and have invited this person to come on a future episode of Teaching on Higher Ed. In the meantime, this episode with Mark Hofer is a good starting point, as is episode 227 with Tom Tobin.

As a former disabilities compliance officer for a university, I would strongly recommend that you do not accommodate a student (for claims of disability) unless required to do so by the disabilities office. There are several reasons why I recommend this stance. 1) You may set up an expectation for the student that she/he will receive the accommodation with other faculty, 2) the student may actually need accommodations better suited to their functional limitations, and 3) the disability office will vet whether the request represents a fundamental alteration to the service or program.

On the flip-side, when a student does have an accommodation that is approved by the disability office, and you have questions about the necessity of that accommodation, you should direct the question to the disability office: not to the student.

In other words, allow the disability office to be the middle-person; they can better help the student AND the faculty member when you do 😉

Dear Scott,

Thanks for bringing these considerations into the conversation. Another person wrote to suggest that I recommend universal design for learning (UDL) to offer a better option than traditional assessment methods afford. She’s coming on the show to share more about that, as a follow up to other conversations we have had about UDL in the past. Another person wrote in with other suggestions. This is such an important conversation – and one I know is only just the beginning of us all doing this better. Thank you for helping us along that path in stressing the importance of not declaring ourselves the office of disability services… which, as you stated, isn’t going to help things, either.