The first time I taught at the college level, I received a call to teach a course exactly five days before it began. I have now taught the same class seven times and each time I teach it, the objectives of the course change. Sometimes these differences have been dramatic, while other times I make a few minor changes to the wording.

Learning objectives are a crucial part of ongoing improvement to my course curriculum and teaching methodology. They steer the direction of a course and help gauge our progress throughout the semester.

What is Important to Learn?

Learning objectives help us to ask, ‘What is most important for students to learn in this class and how will I know when the learning has occurred?’ While there are many definitions used in clarifying learning objectives, the one I have found most useful comes from an expert in the corporate training world.

Mager (1997) defines a learning objective as (p 3):

… a collection of words and/or pictures & diagrams intended to let others know what you intend for your students to achieve.

- It is related to intended outcomes, rather than the process for achieving those outcomes

- It is specific and measurable, rather than broad and intangible

- It is concerned with students, not teachers

Designing Course Objectives

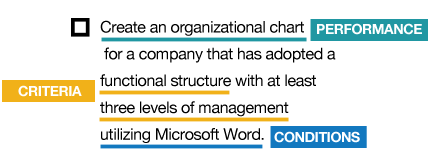

All my course objectives are designed using Mager’s (1997) criteria for a measurable learning objective. Each objective conveys what the learner should be able to do, under what conditions, and how well they should be able to do it. I refrain from using words like ‘understand’ or ‘appreciate’ in my objectives, as they are neither descriptive nor measurable. Mager describes the three components of a useful objective as (p 53):

- Performance. It describes what the learner is expected to be able to do. Use action verbs to ensure clarity (examples of action verbs include: describe, sort, compare, contrast, create, present, explain, list, and solve).

- Conditions. It describes the conditions under which the performance is expected to occur.

- Criterion. It describes the level of competence that must be reached or surpassed.

Here’s is an example from one of my courses:

Performance: Draw an organizational chart is the desired performance, or what the student is expected to be able to do.

Conditions: In the conditions area, certain technical skills are required as part of this learning objective.

Criteria: The criteria in this case is that the org chart they draw contains at least three levels.

The Learning Objective is the Compass

Whenever I am in the process of grading an assignment, the course objectives are in front of me as I gauge the students’ ability to do what is described, under the specified conditions, and to the level of competence required. All objectives are also included in the course syllabus and referenced regularly throughout the semester.

The objectives for my courses rarely go a semester without some form of revision. It is essential that learning objectives change and grow as you teach a different student population. I particularly value:

- assessment results (completed by the student, such as exams, blogs, in-class role plays, and learning portfolios)

- speak with industry professionals and professional associations (which often list their own competencies for professionals in the field).

- alumni (a number of past students are now working professionally in sales and have much to contribute in terms of what is most important) and

- other faculty (to the extent that our curriculum can build upon each others’ classes, we can more effectively build students’ knowledge and skills).

Developing and revising learning objectives does take some thought and effort, though the payoff in clarity of focus and ease of measuring student progress is well worth it.

[…] Revisit learning outcomes […]