Tricia Bertram Gallant

Director

An internationally recognized expert in academic integrity and ethics in higher education. As the Director of the Center for Integrity in Education at the University of California, San Diego, she leads innovative efforts to cultivate integrity-centered learning environments and assessment practices. With a career spanning nearly two decades, Dr. Bertram Gallant has advised universities, policymakers, and global organizations on fostering cultures of honesty and accountability in the face of emerging challenges—most recently, the integration of Generative AI in education.

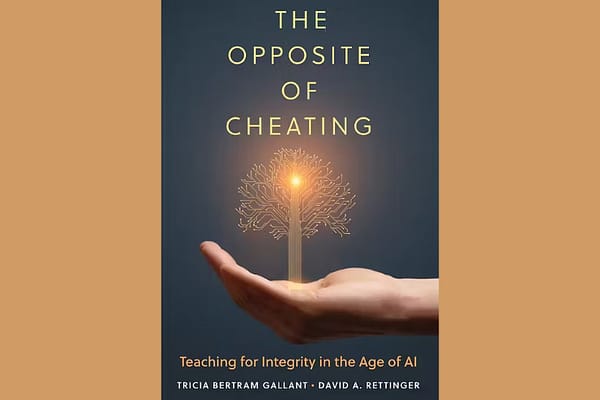

A prolific author, Tricia’s books, including The Opposite of Cheating: Teaching for Integrity in the Age of AI (2025), have shaped institutional approaches to academic integrity worldwide. Her scholarship blends research with practical strategies, making her a sought-after speaker, consultant, and media commentator on issues of cheating, AI, ethics, and assessment security.

Beyond academia, Tricia’s work has influenced national and international policies on academic integrity, including collaborations with the Council of Europe, UNESCO, and the International Center for Academic Integrity. She has delivered keynote addresses and workshops across North America, Europe, Asia, and Australia, engaging faculty, administrators, and students in reimagining integrity for the 21st century.

Known for her engaging, research-driven, and solution-oriented approach, Dr. Bertram Gallant doesn’t just diagnose problems—she helps institutions and educators implement real, sustainable change. Whether as a keynote speaker, panelist, or podcast guest, she brings insight, clarity, and a touch of humor to complex conversations about academic integrity, learning, and AI’s role in education.

David Rettinger

Applied Professor of Psychology

Dr. David Rettinger has taught psychology at the college level for over 20 years, including at the University of Mary Washington and now at the University of Tulsa. He is an expert in students’ academic integrity behavior, having published research in Theory into Practice, Research in Higher Education, Ethics and Behavior, and Psychological Perspectives on Academic Cheating. He is co-editor of "Cheating Academic Integrity: 40 Years of Research” published by Wiley. His research has demonstrated the importance of students’ attitudes toward school and beliefs about peer behavior in determining whether students will cheat.

Rettinger is President Emeritus of the International Center for Academic Integrity, an organization founded to combat cheating, plagiarism, and academic dishonesty in higher education. He leads the organization's efforts in assessment and survey research, continuing the McCabe academic integrity survey.

He has presented on topics relating to pedagogy, policy, and practice in academic integrity around the U. S. and internationally. His collaborations include partnerships in Chile, Mexico, Nigeria, Thailand, and Ukraine and as a Fulbright Specialist in Nepal. He has appeared in numerous media outlets like the CBS Morning Show, The New York Times, The Washington Post, Inside Higher Education, and The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Bonni Stachowiak

Bonni Stachowiak is dean of teaching and learning and professor of business and management at Vanguard University. She hosts Teaching in Higher Ed, a weekly podcast on the art and science of teaching with over five million downloads. Bonni holds a doctorate in Organizational Leadership and speaks widely on teaching, curiosity, digital pedagogy, and leadership. She often joins her husband, Dave, on his Coaching for Leaders podcast.